Notes From the Road: Catching the Anomaly: A Site Identification Trip Through the Rock River Watershed

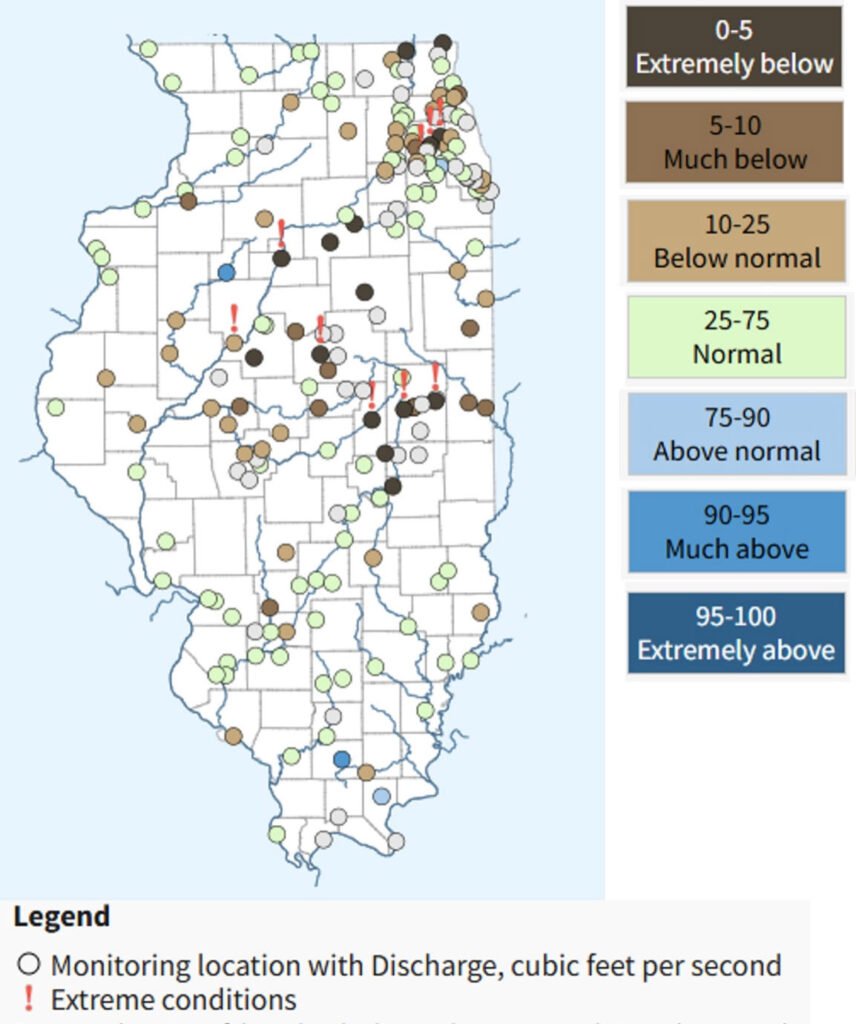

Image caption: image of USGS gage stations throughout the state of Illinois, collecting data through the Water Data for the Nation program. The percentiles indicated by the color of the location ID dot show how a value relates to all the other values for a given day of the year and indicate what percentage of days have an average (mean) value less than the latest recorded value. Extreme conditions (notated by an exclamation point) are indicated when the latest continuous data value is outside of the percentile range of historic daily averages, meaning current conditions are above the highest or below the lowest daily average ever recorded for this day of the year. Image modified from waterdata.usgs.gov.

Earlier this month, Shawn Meyer, Waterborne Lead Scientist and Manager, and I met in Dixon, IL, and spent two days winding our way from the border of Wisconsin to the Mississippi River. We followed the paths of rivers and streams that make up the lower Rock River watershed with a straightforward goal: to identify potential river sampling sites that would help us better understand nutrient loss across this priority watershed in Illinois’ Nutrient Loss Reduction strategy. The purpose of this particular trip was to identify sites that would capture the most representative "signal" of nutrient loads moving through the watershed, while ensuring that locations were safely accessible for consistent, repeatable sampling efforts.

We focused on bridge crossings with existing U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) gaging stations to take advantage of publicly available data. These gages are like time capsules, recording years (and sometimes decades) of streamflow data. Visiting these spots in person helped us assess accessibility and site conditions for future monitoring, but it also offered a rare on-the-ground view of something we usually study on screens and spreadsheets: the rivers themselves.

And what we found was striking. Every site we visited—whether a small tributary or the mainstem of the Rock River—was running exceptionally low. Exposed riffles, sluggish side currents, and wide stretches of visible riverbed provided visual context for what were abnormal levels. When we checked the USGS data later, it confirmed our observations: these were some of the lowest streamflows on record for this time of year.

Moments like this are reminders of why fieldwork is so valuable. We often think of “normal” conditions as the baseline for environmental monitoring, but in reality, there is no such thing as normal anymore. Each year brings its own set of anomalies, whether it’s historic flooding, drought, or unseasonal temperature swings, and these outliers are exactly what make long-term datasets so powerful.

Catching the system in an unusual state, like this year’s low-flow conditions, helps us see how rivers respond under stress. Low water can change everything: how nutrients move, how aquatic organisms survive, and how sediment travels downstream. Documenting those shifts gives us a clearer picture of how climate variability is reshaping our watersheds over time.

Catching the system in an unusual state, like this year’s low-flow conditions, helps us see how rivers respond under stress. Low water can change everything: how nutrients move, how aquatic organisms survive, and how sediment travels downstream. Documenting those shifts gives us a clearer picture of how climate variability is reshaping our watersheds over time.

This trip was more than a logistical exercise; it was a reminder to two seasoned field scientists that spreadsheets of data can't tell the whole narrative. We must revisit the basics of "ground truth" to understand how a watershed in flux responds physically to environmental change. As we plan our future sampling efforts, the data and impressions gathered during these two days will serve as a valuable reference point. Environmental monitoring isn’t just about collecting numbers; it’s about capturing the stories those numbers tell. And this year, the story is clear: even familiar rivers have something new to say when the water runs low, making capturing those “anomalous” years critical.

Growing tea isn’t for the faint of heart

READ MORE

It’s a new year… Time for a Good Laboratory Practices refresher

READ MORE

Celebrating Geographic information systems (GIS). Properly.

READ MORE